Since I don't have any images of nineteenth-century Russian peasant villages,

this photo of a Russian village house in the 1970s will have to do.

By the 1860s, peasants throughout the empire lived in a variety of different circumstances with an accompanying diverse set of legal requirements, but in most cases peasants lived in some form of communal organization. Let's cover some of the terminology.

The mir (мир) was usually used to denote a local, self-governing peasant community at the village level. According to Stephan Merl, in the Encyclopedia of Russian History, vol. 3, pp. 948-49, "the village community formed the world for the peasants where they tried to keep a peaceful society." Merl noted that the mir was a "spontaneously-generated peasant organization" that stretched back in history as far, perhaps, as the eleventh century. By the nineteenth century, the duties of the mir included control of common land and forests, levying recruits for military service, imposing punishments for minor crimes, and collecting and apportioning taxes by the members. To make sure that taxes were equitable, as well as to insure that each peasant household had a sufficient minimal standard-of-living, the mir periodically redistributed the arable land among the households.

The village assembly (the skhod) made all decisions. The assembly was run by the heads of the individual families, i.e., the oldest men, who elected a single elder to represent the village community. Since age tended to be respected, the assembly was generally a very conservative body, frowning upon any ideas of innovation. After the emancipation, the government basically expected the assembly to to take over responsibilities previously held by the landlord and maintain order in the village.

The obshchina (община) is another term that you will often see used to refer to peasant communities in imperial Russia. The word "obshchina" is a bit difficult to translate, but it is generally taken to mean either "community" or "commune." According to Merl, the word obshchina really derived from the 1830s when it was used by the Slavophiles to focus more specifically on the land redistribution function of the village community. By the middle of the nineteenth century, the terms obshchina and mir had become essentially interchangeable.

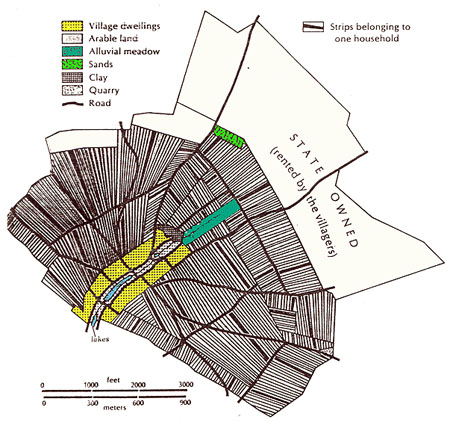

Thus, it is important to remember that by the terms of the emancipation, the land was given to the mir/obshchina not to individual peasants. This meant that the conservative nature of the mir tended to prevent any improvements in agricultural methods. The village assembly decided what crops to grow and regulated crop rotation according to time-proven methods. (See the diagram below.) Because of the nature of the commune holding in which an individual household was given strips of land scattered across the arable land holdings of the commune, all farm work had to be done in common; sewing, reaping, tilling, fertilizing all had to be done at the same time in the same manner. In other words, it did not work for you to plant potatoes on your strip of land in one field while everyone else around you planted wheat. The farms animals and machinery available also meant that everyone had to do the same thing, which tended to be the traditional bare minimum. There was absolutely no incentive to try and improve a particular set of strips because those holdings could always be repartioned to another household.

Illustration of what a Russian peasant commune might have looked like.

There are some other terms that you might run into that deal with

peasant life in the Russian empire. The "pozemel'naia

obshchina" basically just means the repartional commune. A selo

(cело) is

a "village," which can also be called a derevnia (деревня),

and a muzhik (mужик) is a Russian peasant.

Thus, it would not be unusual to refer to a peasant

village/commune/community as a mir, an obshchina, or a selo.

Russian peasant village in winter.