HIS 241

|

|

Historians have traditionally

divided the reign of Alexander I into the good-intentioned first half

followed by the reactionary second half (sound familiar?) with the dividing line being

Napoleon's 1812 invasion of Russia. In the first part of the

reign, the tsar and his Unofficial Committee, composed of Prince Adam

Czartoryski, Count Pavel Stroganov, Count Viktor Kochubei and

Nikolai Novosiltsev considered various reform plans

for Russia. The consideration of reform advanced as far as

Mikhail Speranskii proposing

a constitution for Russia (I have a copy of Speranskii's proposal in Russian, but I have not yet had time to translate it.), but aside from some governmental and

educational reforms, which indeed were important, there were no

fundamental constitutional changes enacted. Historians have come

up with many reasons for the failure of the tsar to actually do

something, including the tsar's own

personality, but you also have to consider that Russia was almost

continuously preoccupied with Napoleon in one form or another from 1798

until 1815. (Already in the Italian Campaign of 1799, Aleksandr Suvorov

(1729-1800) had lead Russian armies to victories against the French in

the wars of the second coalition.) So, the entire first half of

Aleksandr's reign, "the era of good intentions," was spent either being at war

with Napoleon, or technically in alliance with Napoleon after the 1807 Treaty of Tilsit. (Read a short account by a British agent at Tilsit?)

Napoleon's invasion of Russia began on 23 June 1812 (You will occasionally see somewhat different dates ranging anywhere from 21 to 24 June.). Estimates of the size of Napoleon's Grand Armee vary considerably, but historians have generally settled upon the figure of 500,000 men. Just try to imagine the problems of coordinating and supplying an army that large two hundred years ago! The Russians were initially able to field anywhere from 250,000 to 400,000 men to oppose Napoleon (The Russians would be able to increase that number as the campaign went on.). |

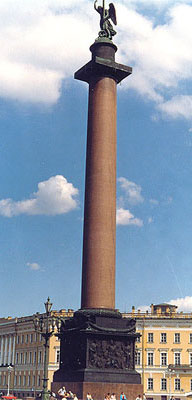

The Narva Gate, erected in St. Petersburg to commemorate the Russian victory over Napoleon. (Some of my pictures are better than others!) |

The Kutuzov equestrian statue outside the Borodino Panorama, located at Kutuzovsky Prospect 38, Moscow (Metro: Kutuzovskaya) |

With the continuing retreat of the Russian army in the face of Napoleon's advance, and with calls for a "Russian" general to take command of the Russian armies, on 17 August the tsar finally appointed Prince Mikhail Kutuzov (1745-1813) as commander-in-chief of the Russian armies. Kutuzov had served with distinction in the Russia military since 1764! But Alexander I had let Kutuzov, popularly known as the "fox of the North," take the blame for the Russian defeat at the Battle of Austerlitz in 1805. (Kutuzov had argued against the allied decision to do battle with Napoleon.) Now it was Kutuzov's turn to deal with Napoleon again. |

After taking control of the Russian armies, Kutuzov continued to retreat until he finally reached a defensive position at the village of Borodino, about 100 km. west of Moscow. There the French and Russian armies met in the Battle of Borodino on 26 August (7 September), the bloodiest single day of battle of the Napoleonic wars. Napoleon, wanting a smashing victory, threw everything that he had at the Russian defensive positions--Not quite, Napoleon refused to commit his elite guard of 25,000 soldiers to the battle. He is reported to have said: "I will not have my Guard destroyed. When you are 800 leagues from France you do not wreck your last reserve"--But the Russian lines held against the French attacks. At the end of the long day of battle, the Russians were still on the field of battle. An inconclusive draw, but in reality maybe an enormous moral victory for the Russians. Under the cover of night, Kutuzov withdrew his forces.The French spent the day after the battle counting bodies and tending wounded.

Casualty estimates for the battle are imprecise. "The French are said to have suffered 28,000 dead and wounded including 48 generals, according to historian Adam Zamoyski." Other estimates put the French losses as high as 50,000. It is generally accepted that the Russians losses were somewhere around 44,000 and 23 generals. That is an extremely high casualty rate for one day of battle.

See also,

- Borodino

- The Battle of Borodino by Baron Lejeune

- Battle of Borodino, a really detailed account of the unit maneuvers during the battle.

Eventually, the Russian retreat continued, and it was decided that there was no way to defend Moscow. So the city was abandoned/evacuated. When Napoleon reached Moscow, he expected Alexander I to meet him and offer a Russian surrender. Napoleon figured that since one of the Russian capitals had been captured, a surrender was in order, but there was no Alexander to be found with the keys to the city or surrender offers. Then fires broke out in the city. (Legend has it that the fires were the result of Russian sabotage; common sense has it that that is what happened when you stick thousands of French occupying soldiers in a deserted city made of wood.) Between 2-6/14-18 September, Moscow almost completely burned to the ground.

With the prospects of winter

fast approaching, Napoleon decided that he did not want to spend the

Russian winter in a burned-out city. On 19 October, Napoleon

abandoned the city and headed towards the southwest, into the

Ukraine where he reasoned he could find provisions for his troops

(remember Charles XII). What sealed the destruction of the French

army, was the

small Battle of Maloiaroslavets,

really just a skirmish, that took place on 24 October. Kutuzov

was able to turn the French from their intended advance southwest back

onto the very same route they had used on their way into Russia, i.e., the

Smolensk High Road. That meant that their would be few supplies for

the French to find on their way out of Russia since they had already eaten everything on their way in. In addition,

Cossacks and other irregular Russian partisan forces could continually

operate against any French stragglers. The French retreat quickly turned bad.

For the French, the ultimate disaster occurred when the remnants of the army tries to cross the ice-swollen Berezina River in Western Russia, while literally surrounded by the Russian army. Really, it was only the incredible heroism on the part of the French engineers and rear guard that saved what was left of Napoleon's army. See,

|

The Crossing of the Berezina by Peter von Hess (1843. Oil on canvas). |

The Russian campaign resulted in an enormous loss of life. Of the 500,000 or more troops that Napoleon counted as part of his invasion force, only about 20,000 maybe left Russia in December 1812. The Russians also probably lost between 400,000 and 450,000 soldiers with accompanying, enormous, and generally uncounted, civilian losses. So, the total campaign casualties were probably easily around a million.

On the Napoleonic Wars, in general, see

- Napoleonic Wars

- Napoleonic Guide

- Napoleonic Wars (These are atlases of all the campaigns.)

- The Russian Campaign, 1812

- The PBS website to accompany their series on Napoleon.

- On the 1812 campaign, there is Project 1812 (in Russian), a small portion of this has been translated at www.museum.ru/museum/1812/English/index.html. The Gallery contains some nice paintings and illustrations, including Fragments from "The Battle of Borodino" Panorama; similarly the Picture Gallery of the 1812 campaign. Check out some more information about the Borodino Panorama Museum; 1812: Napoleon's March to Russia.

- In 1861, Charles Joseph Minard (1781-1870) published his path-breaking graphic on Napoleon's 1812 invasion of Russia. The graphic captured four different changing variables that contributed to [Napoleon's] failure, in a single two-dimensional image [including] the army's distance and direction as they travelled; the altitude the troops passed through; the size of the army as troops died from hunger and wounds; the freezing temperatures they experienced. There are some versions of this "tableau graphique" available now on the web. See, Losses Suffered by the Grande Armée during the Russian Campaign from John Schneider's Napoleonic Literature page; referenced from the Re-Visions of Minard by Michael Friendly. C. J. Minard's Map (Napoleon's March of 1812) is a clickable version.

ps. Well we can't really mention Alexander I

without a quick discussion

of how he ascended to the throne of Russia. Now Catherine the

Great

and her husband, Peter III, who she had killed by her friends,

allegedly had one son (Paul I),

although there were some pretty legitimate questions at the time about whether

Peter III was

the father. It is actually relatively clear now that Peter III was not

the father; so that means that Paul I was not a legitimate male heir,

and thus the Romanov dynasty had come to an end with the death/murder

of Peter III.

With

good reason (the murder of his dad), Paul always resented Catherine

and her entire "enlightened" imperial court. When Paul assumed

the throne

of Russia in November 1796, he brought a new sense of Prussian

militarism to the

country, symbolized by his estate at Gatchina. This was in sharp

contrast to the Frenchified court of Catherine. (He also made sure that

Catherine was buried next to her murdered husband, Peter III, whose

remains were exhumed to also lay "in state" with Catherine!) Paul had always been kept as far away from Catherine as possible, and his oldest two sons, Alexander and Constantine, had been removed from his care. They were personally raised by Catherine and given a liberal and enlightened education. |

Monument to Paul 1 in front of Gatchina. |

Once Paul was tsar, he quickly became very unpopular even though many of the measures that he enacted do not seem to have been all that bad from today's vantage point, such as establishing a male line-of-inheritance to the throne of Russia--easy to understand why he did that--freeing political prisoners, forbidding the working of serfs on Sundays, and so forth. But Paul was also very anti-French and pro-Prussian (and there were a lot of other quirky manners that did not go over well with the imperial court.). Then he led Russia into the Second Coalition against Napoleon and France, only to suddenly changed his mind in 1800 and became friendly with France against Great Britain.

A conspiracy was hatched to remove Paul as tsar with close friends of the now-dead Catherine the Great as the chief conspirators, including Count Pahlen, head of the police and Catherine's last lover, and Count Zubov. "On the night of March 12/24, 1801, Pahlen, Count Bennigsen, and the Zubov brothers Nikolai and Platon entered the Mikhailovskii Castle with the assistance of a co-conspirator, an unfaithful aide-de-camp of Paul's. They found the tsar's bed empty. The conspirators, who were drunk, found their head of state hiding behind a screen in his chamber. In an alcohol induced frenzy, they proceeded to murder the man to whom they had sworn their loyalty." (www.alexanderpalace.org/palace/Paul.html) The extent of Alexander's actual involvement in the plot against his dad remains a bit unclear since Count Pahlen destroyed any surviving evidence of the conspiracy. Perhaps Alexander had thought that his father would just be forced to abdicate; instead his dad was killed. The Russian public was just told that Paul died from a "cold" (Ok, I exaggerate a bit! The official announcement was "apoplexy.").

Some websites about Paul and the palace at Pavlovsk:

- Monarch Idealist – Emperor Paul I of Russia Emperor Paul I

- Emperor Paul I

- Pavlovsk Palace

- Pavlovsk

- Pavlovsk

- Allen McConnell, Tsar Alexander I: Paternalistic Reformer (1970)

- Michael Jenkins, Arakcheev: Grand Vizier of the Russian Empire, a Biography (1969)

- Evgenii Tarle, Napoleon's Invasion of Russia, 1812 (1959)

- Marc Raeff, Michael Speransky, Statesman of Imperial Russia, 1772-1839 (1957)

- Christopher Duffy, Borodino and the War of 1812 (1973)

- Richard Pipes, [Karamzin's] Memoir on Ancient and Modern Russia (1811)

- Some lectures by the late Professor Michael Boro Petrovich are available on the web: Paul, Alexander I, and Alexander and Napoleon.

- Alexander the Sphinx, remarks by Professor Gerhard Rempel, Western New England College.

- The two primary residences associated with Alexander's father, Paul I were Pavlovsk and Gatchina.

- Two descriptions of Alexander II include: Czartoryski's Description of Alexander I and his Reforms and An Austrian View of Alexander I and the Russians at the Congress of Vienna, 1815.

- Biblioteka proekta 1812 (in Russian) is an online archive or resources about the 1812 campaign.

- Finally, with regard to the campaign of 1812, see these short sites: Napoleon's Invasion of Russia and Prince Mikahil Illarionovich Kutuzov.