The grave of Alfred Dreyfuss (and family) in Montparnasse Cemetery, Paris.

Photo John and Melanie Rosenthal.

Over the course of the nineteenth century, the map of Europe changed quite dramatically as many new countries came into existence: Germany, Italy, Serbia, Bulgaria, Romania, etc. In most cases, the appearance of these countries was the result of national unification/liberation movements that had been inspired by the nationalist rhetoric of the French Revolution. Well, the nation-building enterprise undertaken by European countries proved to be a not-so-simple-undertaking. Even after a country had been created, it was not so clear that everyone in that country agreed with a single definition of the "nation" or that everyone actually wanted to be part of that "nation." Indeed, it may seem surprising that is was in France itself--the birthplace of the French Revolution and the home of the Enlightenment philosophes--that a major political/ideological challenge to the legitimacy of the French Republic arose. That challenge was connected with the name of a hardworking, unassuming, young, Jewish artillery captain from Alsace, a province of France until 1871.

![]()

In the summer of 1894, Major Count Ferdinand Walsin-Esterhazy, a French officer of dubious means, walked into the German embassy in Paris and offered to sell secret military documents to Germany. From this rather inauspicious beginning, a major sociopolitical scandal evolved that rocked the French Third Republic to its very foundations in the ensuing decade.

When the French intelligence service discovered that someone was leaking secrets to the Germans, instead of conducting a rigorous investigation to determine the identity of the traitor, French officers settled the blame on Captain Alfred Dreyfus, a young Jewish officer (not an aristocrat) from Alsace. Despite no real concrete evidence and conflicting hand-writing analysis, Dreyfus was court-martialed, found guilty and sentenced to imprisonment on Devil's Island. The trial was largely orchestrated by the French High Command--in fact, the military court was secretly ordered to convict Dreyfus--to use Dreyfus as a convenient scapegoat, since the real traitor had not yet been found, and there was not much of an effort undertaken to find the real culprit.

Professor Montaner adds:

Alsace is a Germanophone region of France bordering Germany. Also, Alsace was one of the region of France with the largest Jewish communities. Finally, at this time France was subject to a strong anti-semitic current that stemmed from a deeply rooted hostility in anti-Judaism. My point is that Dreyfus was the perfect scapegoat for the people who were suspicious towards the Jewish community (and there were legions!). Also, the Alsatian origins of Dreyfus made plausible affinities with Germany.

French Jews were traditionally very patriotic and deeply attached to the nation that emancipated them during the French Revolution. For the first time in French history, Jews were considered as true French citizens. This, in turn, lead to an ardent devotion of the French Jews towards the Republic. The Dreyfus affair was the first clear sign that the Jews of France were still not considered as true patriots and were discriminated against. I guess we could point out that antijudaism and antisemitism (the hatred of the Jews based on racial and not religious criteria, backed up by pseudo-scientific facts), were deeply rooted in the French population of the end of the 19th century.

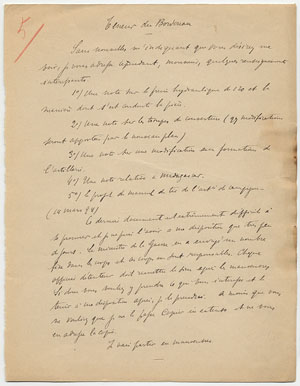

Source for the Bordereau en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Bordereau.jpg

Here is a picture of the "bordereau" which the French military high command alleged was written by Dreyfus and then was used by the military to convict Dreyfus of treason. In fact, the small paper contained a list of possible documents that Esterhazy was willing to turn over to the Germans for an amount of money to be determined later. In reality, none of the artillery documents listed here were of any real value, and most were hardly even secret. Amazing that this small list written by Esterhazy caused so much trouble!

Two years after the trial of Dreyfus, some evidence was discovered that actually revealed Esterhazy as the source of the "bordereau," but that evidence was suppressed. By that time, some French intelligence officers had been busy manufacturing all kinds of materials to cover up Esterhazy and further incriminate Dreyfus. To clear his name, Esterhazy was acquitted after a military trial--most of the real facts about Dreyfus still remained hidden.

As the French General Staff and military intelligence, which was directly connected to the French Minister of War, continued to assert Dreyfus' guilt, efforts to reverse the verdict slowly took form, even though it was a daunting task. One of the first politicians/journalists to rally to the side of Dreyfus was Georges Clemenceau, later know as "the Tiger" and the man who oversaw the French victory over Germany in World War I. As a left-wing radical, he deeply distrusted the political motives (anti-republic) of the country's conservative right wing and church in supporting the Dreyfus conviction.

French politics soon had become deeply divided between supporters of Dreyfus as guilty (These anti-Dreyfusards tended to be anti-republic, pro-Catholic, with monarchist, or dictatorial, leanings.) versus supporters of Dreyfus as innocent (The Dreyfusards, or revisionists, tended to be pro-republic, socialist, radicals and anti-church). This division mirrored long-standing fissures that had been lurking under the surface in France after the catastrophic defeat at the hands of the Germans in 1870-71. At one point, in 1889, it looked as if Georges Boulanger (1837-1891) was about to seize power and establish a right-wing, military dictatorship. Boulanger was a "popular" military officer and later war minister who had fought with distinction in 1870-71 and also gained notoriety for his ruthless suppression of the Paris Commune in 1871. At the key moment in 1889, Boulanger fled the country, leaving his supports astonished and angry. The Dreyfus Affair gave those supporters and other "disenchanted with the republic" political elements an opportunity to unite against the republic.

At first there were very few Dreyfusards, but they slowly grew in number as more people began to realize the dangers to the French Republic of the Anti-Dreyfusards.

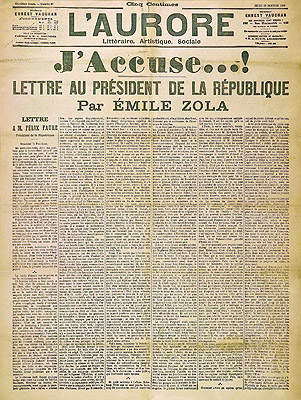

Zola's article; source upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/b/b4/J_accuse.jpg

Then, Émile Zola got involved in the Affair. Zola was at the height of his worldwide literary fame, and he became convinced of the innocence of Dreyfus. He was aghast at the extent of the government/military cover-up. After long contemplation of exactly what he could do, on 13 January 1898, he published an open letter to Félix Faure, the president of France. In the letter, Zola ridiculed the case against Dreyfus and accused a whole series of people from the president on down of allowing the injustice to take place. To the left is an image of the paper with the famous headline "J'accuse!" (I accuse!) that Clemenceau had brilliantly devised for the article.

Incredibly, the French government responded by bringing charges of libel against Zola--the charge was not for the entire article but for only one particular passage: "only that passage of "J'accuse" in which the author stated that a court-martial 'acting on orders' dared acquit Esterhazy. This would give Zola the right to produce evidence against Esterhazy but not in favor of Dreyfus." (Nicholas Halasz, Captain Dreyfus: The Story of a Mass Hysteria, p. 137)

Zola's trial began on 7 February 1898 amidst vociferous public protests and demonstrations--mostly against Zola--and he was found guilty on 7 February 1898. Zola immediately fled to England to avoid going to prison in France. World opinion was shocked at the stunning guilty verdict. Zola was able to return to France in the summer of 1899.

Despite new "evidence" presented at a second military court-martial, Dreyfus was again convicted in September 1899, but slowly the public tide was turning, and pro-Dreyfus sentiments grew stronger. Eventually, the case ended up in the hands of France's supreme court. In July 1906, the court ruled Dreyfus not guilty. (Read the description of the acquittal (Halasz, Captain Dreyfus).)

In a way, it was rather fitting that Dreyfus himself played so little of an active role in the entire political struggle in France--he was in prison throughout, and when he was not in prison, he was a passive agent awaiting the outcome of the affair. The Dreyfus Affair, as it evolved from a simple "who was selling secrets to the Germans" to a question about the future of the French Third Republic, "whether it could continue as a republic based on law or would be replaced by a right-wing dictatorship," entailed questions far beyond the relatively straight-forward question of his innocence or guilt.

Indeed, Clemenceau

had not shared his friends' disappointment over the fact that Dreyfus in person had proved so inadequate to the part that he had been chosen by fate to play. "It is better this way,' Clemenceau had said. "At least no one will accuse us of having hurled ourselves into the battle for reasons of personal sympathy." (Halasz, Captain Dreyfus, p 262)

![]()

There are wiki entries (both in English and en français) for all of the principle figures:

- J'Accuse (en français); see also the Text of J'accuse! (English translation side-by-side with the French original) by David Short

- Alfred Dreyfus (en français)

- Émile Zola (en français)

- Georges Clemenceau (en français); see also The Clemenceau Museum

- Ferdinand Walsin Esterhazy (en Français)

- Maximilian von Schwartzkoppen (auf Deutsch)

- Dreyfus Affair (en français with an excellent bibliographie)

- Marie Georges Picquart (en français)

- Picquart's Investigation of the Dreyfus Affair

- Devil's Island (en français)

- L'Aurore (en français); There are digital copies available via Gallica which is the digital library part of la Bibliotheque nationale de France (English search version).

Other online sources

- Dreyfus Réhabilité (English version). This is a great website from the French Ministry of Culture with all sorts of materials, in different media formats, about the Affair.

- Dreyfus, Alfred (1859-1935), very short entry on the Dreyfus Affair by the Jewish Agency for Israel; similarly Alfred Dreyfus and “The Affair” by the Jewish Virtual Library

- Note that Google books has excerpts from a number of books dealing with the Affair, for example, France and the Dreyfus Affair, A Documentary History by Michael Burns

- The Alfred Dreyfus Trials: Selected Links and Bibliography by Nancy Morgan (really just links to a select few websites)

- The Dreyfus Collection in the The Department of Special Collections and Archives, The Johns Hopkins University, contains twenty-nine original drawings and sketches by various artists of figures connected to the Dreyfus Affair. (No longer available online)

- Beyond the Pale: The Dreyfus Affair is a two-page summary, with some images, that is part of a larger work entitled The Development of Modern Anti-Semitism

- Adam Gopnik, Trial of the Century: Revisiting the Dreyfus Affair, The New Yorker, 28 September 2009

- The Dreyfus Affair: Chronology established by Dr. Jean-Max Guieu, Georgetown University

- Donald E. Wilkes, Jr. J'accuse...!" Emile Zola, Alfred Dreyfus, and the Greatest Newspaper Article in History (1998), is a short article by a professor of law.

- Robert Wernick, Count No-Count Esterhazy, The Man Who Created the Dreyfus Affair (Smithsonian Magazine, 1989)

- The Dreyfus Case, September 9, 1897, The New York Times Archives. I think that you can follow coverage of the Dreyfus Affair in online versions of the New York Times archives.