The caption to this photo reads: Field of millet.

Picture of a horseman in a millet field in 1896 or 1897 in West Africa. Millet is a cereal grass commonly used to make a flour in West Africa. First, the millet seeds are ground in mortars by women, and then the flour is used in food preparations.

The caption to this photo reads: Karamakobilé, chief Moor of Bamako [Mali, 1883].

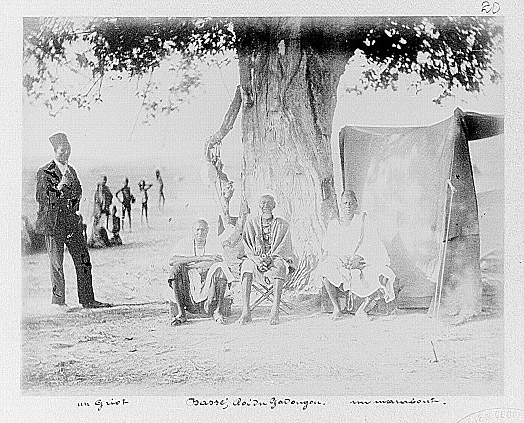

The caption to this photo reads: a griot, Bassé, King of Gadougou, a marabout.

In traditional West African society, kings or nobles were usually accompanied by "griots" who played a very important role in the court of a king as spokeperson and ambassador of the king. They were also skilled musicians, poets and the official historians of the kingdom. Griots played a similar role with the heads of noble families and other powerful men such as colonial interpreters like Wangrin.

The importance of griots can be understood by the fact that when a griot would propose his service to a man, the latter would have no other choice but to listen to the entertaining musical and poetic performance of the griot. The listener would also have to provide the griot with gifts as payment or as a sign of gratitude. Griots would often look for wealthy travelers and inform them on the customs of the locale. They would also serve as guides for foreigners.

Marabouts were another type of learned men in West Africa. They were highly respected for their knowledge in medicine, religion or any other type of traditional knowledge. Marabouts were not supposed to ask for payment for their services, but they were usually given gifts by the people they assisted.

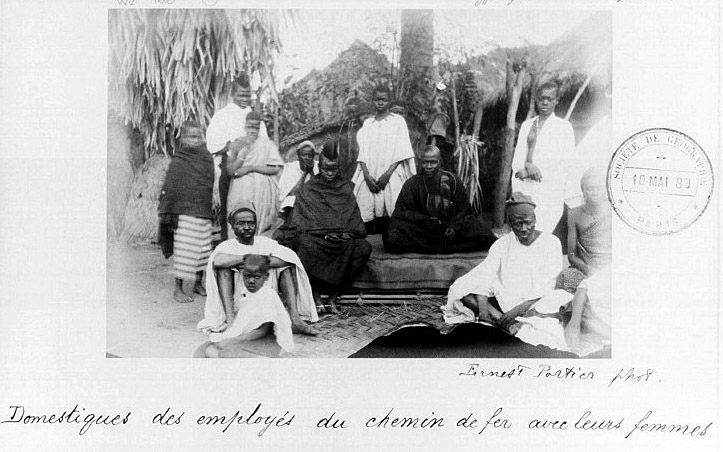

The caption to this photo reads: Servants of railroad employees with their women [in Kayes, Mali].

In colonial French West Africa, the traditional hierarchy of the African society got reshuffled into two main groups: the group of the French citizens and that of the French subjects.

The French citizens were at the head of the colonial society. Within this group, several layers can be distinguished:

1. “les blancs-blancs” or “white-white”

The French Europeans, usually working for the colonial administration, the French military or French companies. They were the all powerful.

Other white Europeans also had more rights or authority than any African.

2. “les blancs-noirs” or the “white-black”

Africans from the “Quatres Communes” (Four districts) of Senegal (St Louis, Gorée, Dakar and Rufisque) who became French citizens in 1916 and had a representative at the French Parliament.

The second group, that of the French subjects, included the following sub-groups:

1. “les blancs-noirs” or the “white-black”

All employees of the French colonial administration, the military or French citizens were deemed more important than other Africans. Their prestige and authority directly resulted from the person for whom they were working.

2. “les noirs-noirs” or “black-black”

All other Africans living in a French territory. They bore the brunt of the suffering caused by colonization.

Source: http://visualiseur.bnf.fr/CadresFenetre?O=IFN-7702495&M=imageseule

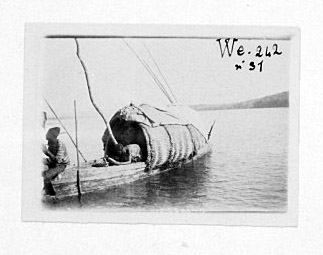

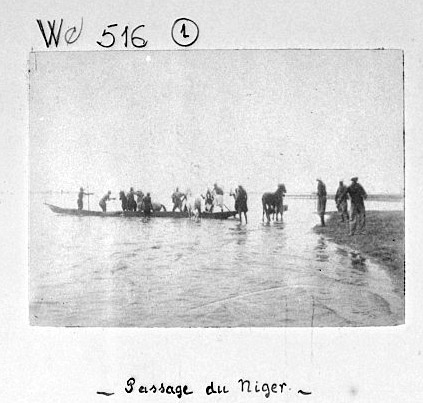

The caption to this photo reads: crossing the Niger river [1896-97].

Most of the transportation on the Senegal or Niger rivers was made in dugout canoes. Very few steam boats were used on those rivers. The crews of those canoes would sing songs in order to work at the same rhythm. Specific religious practices were also associated with that trade of boatsman. For instance, at the junction of the Niger River (the White Niger) and one of its affluents, the Bani or Black Niger, travelers and crew had to throw offerings to the deity of the river in order to guarantee safe passage.

The caption to the photo simply reads, "The Niger" [1898-99].

Some of the dugout canoes could accommodate more passengers and larger amounts of cargo and could have a covered section.

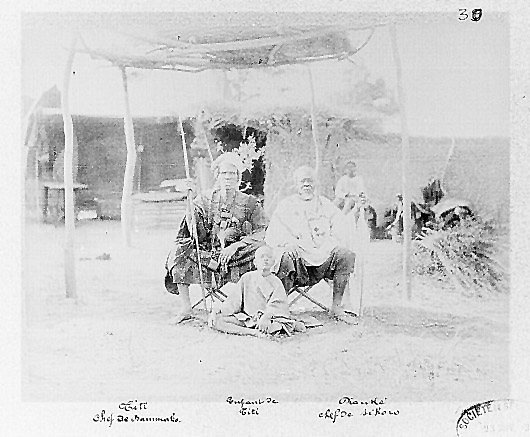

The caption to this photo reads: Titi, chief of Bamako, child of Titi, Dianké, chief of Sikoro.

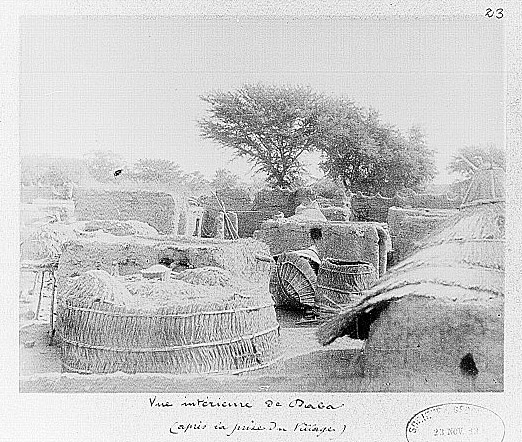

This photograph illustrates what was called a “concession” or residence. Such traditional habitat was usually built in a vast space that was of rectangular or square shape. All was built on the same ground level. The entrance of a “concession” would usually have a vestibule or hall leading to the inside of the property where the rooms were centered around a courtyard. Given the structure of the traditional African family, each “concession” was usually the home of large families. Men, women, teenagers and servants lodged in different spaces. Festivities, cooking, meals and most household activities were usually held in the central court. The court was really the place where people lived. Such habitations were usually made with whatever materials were available locally.

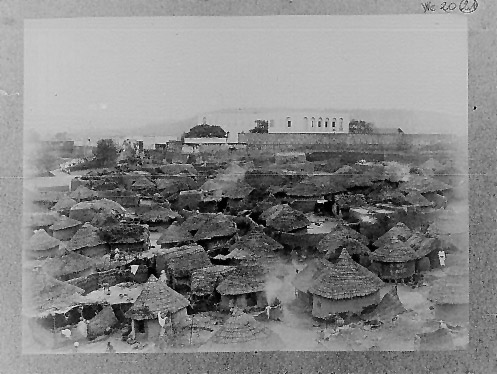

The caption to this photo reads: View of the inside of the village of Daba (after the capture of the village) [1883].

This photograph shows a traditional village with “cases” or huts made of mud and fodder with a characteristic round shape and a conical roof.

Source: visualiseur.bnf.fr/CadresFenetre?O=IFN-7702019&M=imageseule

The caption to this photo reads: View of Sakel [Senega, 1882].

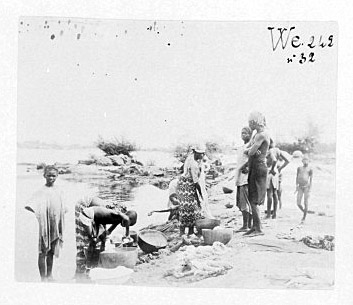

The caption to this photo reads: The Women doing the laundry on the shore of the Niger River.