The "Silver Age" of Russian culture--sometimes this is more restricted to the "silver age of Russian poetry"--was supposedly not quite as brilliant as the Golden Age which preceded it. In my view we could say that the Golden Age featured the novel and the symphony, while the Silver Age centered on the poem and the stage. I have always found the Silver age to be far more dynamic and interesting, as the new artistic forms of the age were really very avant garde and cutting edge in poetry, ballet, drama, music, dance and modernist art. There were also some very bizarre views of the world advanced by the artists.

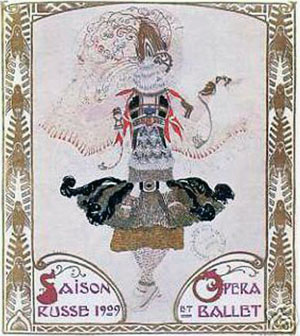

Ballet Russes Illustration

For my sake, I'm going to restrict my comments on the Silver Age to the period between 1898, when the journal Mir iskusstva (World of Art) first appeared, until 1914 and the outbreak of World War I. This was a very dynamic, creative intellectual period, a time of experimentation with different art forms and with breaking the rules of traditional art in the visual, literary and performing arts.

You probably have already heard of some of these Russian artists.

Music

- Aleksandr Skriabin (1872-1915) was the foremost symbolist composer of his age. A gifted pianist he is most know for his piano compositions, but he also experimented with multimedia and color in his work, and some of his performances were accompanied by color projections on a giant screen. He thought he could bring about the end and rebirth of the world through a grand performance including music, scent, dance, and light that would take place in the Himalayas.

- Igor Stravinskii (1882-1971) was one of great composers, pianists and conductors of the twentieth century. His path-breaking ballet works Le sacre du printemps (The Rite of Spring, 1912-13)--Most people know this work from Walt Disney's Fantasia (1940)--and L'oiseau de feu (The Firebird, 1910) were crafted for Sergei Diaghilev's Ballets russes.

- You might also bend the rules here and include Sergei Rachmaninov (1873-1948) as part of the Silver Age. He was one of the foremost pianists of his age and a composer of piano pieces, sonatas, operas, preludes, and Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini.

Art

- Vasilii Kandinskii (1866-1944)

- Marc Chagall (Mark Shagal, 1887-1985) who began to paint at this time

- Kazimir Malevich (1878-1935), painter, art theoretician and developer of abstract geometric art

- Mikhail Vrubel (1856-1910), associated with the World of Art journal

Literature

- Maksim Gorkii (1868-1936)--probably one of my favorite Russian authors--was

publishing his short stories and then Mother (1906). He was path-breaking

exactly because of his realism, his depiction of the "lower depths" of Russian society.

- Mikhail Artsybashev (1878-1927), author of Sanin (1908), scandalous novel in which the "hero" travels the Russian countryside seducing innocent girls; rather graphic for the time.

- Leonid Andreev (1871-1919), playwright and author of short stories, including The Seven who Were Hanged (1908)

I've mentioned the World of Art (Mir iskusstva) journal (published between 1898 and 1904) several times now in these courses, and I use its appearance as dating the start of the Silver Age, and coinciding with the height of Russian symbolism. The journal was co-founded in St. Petersburg by Alexandre Benois (1870-1960), Lev Bakst (1866-1924) and Sergei Diagilev (1872-1929). They intended to promote artistic individualism and the idea of art of art's sake--instead of art for Russian national purposes--and push back the boundaries of acceptable art. This was the onset of a new artistic attitude that found its most pronounced expression in performance (ballet and drama) and poetry (also a form of performance)--that remains a bit striking to me.

Ballet

I am working on a separate page for this right now.

Drama

Anton Chekhov (1860-1904) wrote a series of

important plays: The Seagull (1896), Uncle Vanya (1899-1900),

Three Sisters (1901) and The Cherry Orchard (1904)--Got to say that

I am not exactly a

big fan of Chekhov's drama, but I do enjoy his short stories. Chekhov's

works proved to be a triumph for the Moscow Art Theatre--still around today--founded

in 1898 by Vladimir

Nemirovich-Danchenko (1853-1948) and

Konstantin Stanislavskii

(1863-1938) who became the century's most influential theorist on

acting. (You can read a bit about his "system," which required an actor

to imagine "what if I were in that situation.")

Poetry

It is extremely difficult to give a flavor of just exactly what was

being accomplished by Russian poets during the Silver Age, but the

primary literary movements were termed Symbolism, Acmeism and Futurism.

There were other smaller poetic schools, such as "mystical anarchism." Numerous

poets were at their peak, and some were just beginning their

careers. (I've provided links to their wikipedia entries as good

starting points for further information on each poet.):

- Ivan Bunin (1870-1953), first Russian to win the Nobel Prize for Literature

- Marina Tsvetaeva (1892-1941), later hung herself after returning to the Soviet Union in the late 1930s

- Anna Akhmatova (1889-1966), one of the "survivors," the standard bearer for the symbolist movement and the traditions of the pre-Soviet Russian intelligentsia until her death

- Boris Pasternak (1890-1960), most known for his novel, Dr. Zhivago (1957), but a superlative poet. My Sister Life (1917, published in 1921), is one of the most important collections of Russian poetry ever published. Forced to decline the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1958.

- Osip Mandel'shtam, (1898-1938), one of the founders of the Acmeist Movement in Russian poetry in 1913, later died in a Stalinist Labor camp. His wife, Nadezhda Mandel'shtam recounted their lives and the horrors of life in Russia in the 1930s in her memoirs, Hope against Hope and then Hope Abandoned.

- Dmitrii Merezhkovskii (1865-1941), one of the pre-eminent symbolist poets and also an author of historical novels, married to Zinaida Gippius (1869-1945), another poet

- Mikhail Kuzmin (1872-1936), symbolist poet, playwright and critic who expressed homosexual themes in his work--first time by a Russian writer

- Nikolai Gumilev (1886-1921), founder of the Acmeist movement along with Mandel'shtam. "At that period, he became a victim to mystification and fell in love to a non-existent woman Cherubina de Gabriak. On November 22, 1909 he had a duel with Maximilian Voloshin over this affair." Gumilev was twice decorated for bravery while serving in the cavalry in World War I; executed by the Cheka in 1921.

- Maksimilian Voloshin (1877-1932), gifted poet, literary critic, translator and water color painter

- Sergei Gorodetskii (1884-1967), another co-founder of Acmeism

- Fedor Sologub (Fedor Teternikov, 1863-1927), symbolist poet, novelist and translator whose major work was the novel, The Petty Demon (Mel'kii bes, 1902) that deals with the travails of a provincial school teacher who gradually becomes paranoid and violent. He was said never to have been seen laughing during the whole of his life.

- Konstantin Bal'mont, (1867-1942), world traveler, prolific symbolist/impressionist poet who believed in "mystical inspiration," an eternal pessimist. Left Russia in 1921 for Paris.

- Valerii Briusov (1873-1924), often cited as the most important poet of the Russian symbolist movement, really beginning the movement with his collections of poems published in 1894-95. "Mystification."

- Viacheslav Ivanov (1866-1949), symbolist poet, translator, philosopher and critic. Spent most of his early life abroad before his return to St. Petersburg in 1905 where he maintained a dazzling literary salon frequented by most of the poets in residence in the city. He left Russia in 1924; later converted to Roman Catholicism.

Ok, these are the big three:

Vladimir Maiakovskii, (1893-1930), early on he became a political radical and then Marxist. His first poems appeared in 1912 in a Russian Futurist journal. One of his most important poems, A Cloud in Trousers (1915) was very long and unbelievably difficult to read--I have tried repeatedly--largely because it was filled with street slang, weird metrics and subtle plays on the grammar of the Russian language, which largely escaped my abilities to figure it out. During the 1920s, Maiakovskii was one of the most prominent intellectuals working for the Soviet regime and trying to define a new "communist futurism"--he was even able to travel abroad because the Soviet leadership "trusted" him, but he became increasingly disillusioned with Bolshevism (see his satirical play The Bedbug (клоп, 1929), also largely unreadable in English). On 14 April 1930, Maiakovskii shot himself. An unfinished poem in his suicide note, written with his own blood, read, "The love boat has crashed against the daily routine. You and I, we are quits, and there is no point in listing mutual pains, sorrows, and hurts."

Andrei Belyi (Boris Bugaev, 1880-1934), novelist, poet, theorist, and literary critic. Belyi drew from several different creative sources for his work, especially the mysticism of Vladimir Solovev (see below) and the work of the symbolists, and his works tended to be both mystical and musical at the same time. In his most important, and disturbing, novel, Petersburg (1913), sounds often evoke colors--you can't translate that--and the entire novel reads like a musical creation. Note: Belyi wrote four symphonies, but not musical symphonies, novels. Another one of his novels, The Silver Dove (1910), is filled with images of Russian mysticism.

Aleksandr Blok (1880-1921) emerged as the leading poet of the Silver Age, respected by virtually everyone. His 1904 collection of poems, dedicated to his wife, Stikhi o prekrasnoi Dame (Verses on the Fair Lady)--some critics have considered as the pinnacle of the symbolist era. The poems are filled with the imagery of color--again hard to translate. By 1917 Blok was traveling in radical political circles, but he had premonitions that something terrible was about to happen to Russia. In 1918, he published his lengthy poem, The Twelve (1918), one of the most controversial Russian poems ever created. Blok described the march of twelve Bolshevik rapists and murderers--the Twelve Apostles--through the streets of Petrograd in the midst of a blizzard--Blok was ambivalent to the city of Peter the Great, much as Pushkin had been in his poem the Bronze Horseman. Blok's poem always reminded me of the mood of final retribution depicted by Michelangelo in his painting of The Last Judgment. Blok's poem was also not a good way to get along with the new Bolshevik regime.

So you might ask how you can better sample and appreciate some of these Russian works from the Silver Age. I don't think that you have any trouble listening to some of the musical compositions, and you can easily have a look at some of the art. That is accessible, as are the ballets--maybe no longer in the original choreographies. Chekhov's drama is a bit more problematic, but his short stories and the works of Gorkii are readily approachable. (Have a look at the movie Detstvo Gorkogo, The Childhood of Maksim Gorkii, 1938.)

Although some of this poetry might not translate well, especially the poems that rely on their lyrical nature or that are dependent on their colors and sounds--In other words, almost all of the poems--the ideas in these works often do translate. Take for example, Vladimir Solovev (1853-1900), often called a kind of secular monk, who was one of the most important inspirational forces for the Silver Age. He devoted his life to his intellectual pursuits and the attempt to come up with a new Christian world view. He had the idea that the world was the "absolute in the process of becoming," and he also propounded his very popular idea of a divine Saint Sophia, the world soul, the eternal feminine principle, the female world soul. His ideas were just as obscure and radical in Russian as they are when you read them in English, but definitely worth reading.

Finally, what has always appealed to me in studying the Russian Silver Age is the lives of these artists, and especially the poets, who grappled to find meaning in their world and searched for the appropriate artistic expression to provide insight and have fun while living through their tangled (and sometimes shattered) personal lives and in the midst of the events taking place in Russia.

- Leonid Andreev, The Seven That Were Hanged (1909)

- Andrei Bely, Petersburg (1912)

- Vladimir Maiakovskii, A Cloud in Trousers (1915)

- Maksim Gorkii, Autobiography of Maxim Gorky combines his previously published My Childhood (1915), In the World (1917) and My University Days (1923). Try to find a copy of his short story, "Twenty-six Men and a Girl."

- Sharon Carnicke, Stanislavksy in Focus (1998)

- Vsevolod Meyerhold, various collections available such as Meyerhold on Theatre (1991)

- Nikolai Berdiaev, wrote a lot, including The Origins of Russian Communism (1937), The Fate of Man in the Modern World (1935), The Beginning and the End (1952), The Meaning of the Creative Act (1954), The Russian Idea (1946)

- Martin Rice, Valery Briusov and the Rise of Russian Symbolism (1975)

- Lynn Garafola, Diaghilev's Ballets Russes (1989)

- Nikolai Gumilev, The Pillar of Fire and Other Poems, translated by Richard McKane (1999)

- Wassily Kandinsky, Concerning the Spiritual in Art (1912)

- Avril Pyman, A History of Russian Symbolism (1994)

- Vekhi (1909); The most recent English version is Vekhi Landmarks: A Collection of Articles about the Russian Intelligentsia (1994)

- Regarding ballet and dance of the Silver Age, have a look at

- the two main ballet companies in Russia, the Bolshoi and the Kirov

- Vaslav Nijinsky: Creating a New Artistic Era

- Anna Pavlova

- For art, check

- Drama,

- Faberge,

- Faberge Eggs, Mementos of a Doomed Dynasty

- Hillwood Museum, the former home of Marjorie Merriweather Post, has a nice collection of Fabergé eggs

- Music,

- Igor Stravinsky (Religious Works)

- Milestone's of the Millennium, Igor Stravinsky's "The Rite of Spring"

- Igor Stravinsky

- The Rachmaninov Society

- Alexander Scriabin

- Thought,

- Michael Epstein, The Basic Ideas of Four Russian Thinkers: Brief Outlines, Vladimir Solovyov, Nikolai Fedorov, Vasily Rozanov, Nikolai Berdiaev

- Vladimir Solovyov

- A. Bergson, Creative Evolution (in Russian)

- Literature,

- Mayakovsky and His Circle

- Maxim Gorky, "Twenty Six Men and a Woman"

- Anton Checkhov, also other biographies at www.kirjasto.sci.fi/tsehov.htm and mockingbird.creighton.edu/NCW/chekhov.htm

- Portraits of Blok and Balmont

- Lindsay Malcolm The Silver Age of Russian Poetry.