|

|

PLEASE

NOTE: Use Internet Explorer or a version of Netscape earlier than 6

to view this page properly...

Back to the Workers' Theatre page...

This part of the class, on the Federal Theatre Project,

was developed for the ![]() Project, Northern

Virginia Community College.

Project, Northern

Virginia Community College.

Click for "Introduction to Theatre on the Web" Main Page

This page last modified: November 17, 2007 .

[PLEASE NOTE: if links on this page take you to external sites, you will have to use the <BACK> key to return to this page. Some of the links will take you to sites made specifically for this page; you may use the link at the bottom of those pages to return here...]

INTRODUCTION

During the late 1920's and early 1930's, an important theatrical movement developed: The Workers' Theatre Movement (clicking here will take you to a page describing significant aspects of that movement.). It eventually diminished in importance around the middle of the 1930's, and one of the developments aiding the decline of the Workers' Theatre Movement, by using many of its methods and theatrical devices, was the formation of the Federal Theatre Project. Once the government took on the task of putting people to work producing theatre, it was able, in part, to subsume the movement. The Federal Theatre Project attempted to put unemployed theatre workers back to work (popular radio and talking movies has virtually replaced vaudeville as America's favorite forms of entertainment, and most vaudevillians saw their jobs disappear); the FTP tried, further, to present theatre that was relevant--socially and politically, was regional--reflected its local area, and had popular prices--many of the shows were free. Most of its famous productions, although not all of them, came out of New York City: New York had a classical unit, Negro unit, and units performing vaudeville, children’s plays, puppet shows, caravan productions, and the new plays unit. The Federal Theatre Project was the only fully government-sponsored theatre ever in the United States.

BACKGROUND

The decade of the 1920s was an era of apparently prosperous but in fact endangered economy; weaknesses in the agricultural system and the dependence on an industrial urban machine lead to the stock-market crash and Great Depression in October 1929. By winter 1930-31, 4 million were unemployed; by March 1931, 8 million. Herbert Hoover did apparently little, thinking prosperity was just around the corner. By 1932, when Franklin Delano Roosevelt was elected, the national income was half that of 1929; there were 12 million unemployed (one of four). Within two weeks of his inauguration, in 1933, FDR reopened three-fourths of the Federal Reserve Banks and continued to try to fix the economy.

Many called FDR's administration "the Alphabetical Administration"--it was often ridiculed because it seemed to have so many different organizations designated by different groups of letters. For instance, the C. C. C., the Civilian Conservation Corps, started in 1933 and found jobs for over 250,000 men. Further, The National Recovery Administration, or N.R.A., also started in 1933 and put 2 million people to work in forest preservation. The Federal Emergency Relief Act, or F. E. R. A., started in 1933, headed by Harry Hopkins, who was a friend and former campaign manager of FDR, put $500 million back into circulation. By 1933 the economy had recovered a bit, but reforms quickened the recovery even more. One of those reforms was the W.P.A.

The W. P. A., or Works Progress Administration, was started in 1935 to give jobs to unemployed people in their areas of skill; this was also headed by Harry Hopkins. There were four arts projects formed for white-collar workers: Art, Music, Writers, and Theatre. The four arts projects spent less than 3/4 of 1 percent of the total WPA budget, yet were blamed for being un-democratic and wasteful. Most blame fell on the Federal Theatre Project [this link takes you to the American Memory, New Deal Collection page at the Library of Congress]--formed August 27, 1935, with its first production in 1936, it remained in existence until 1939. It employed 10,000 people per year on average; up to 12,000 people at its highest. The Federal Theatre Project [this link takes you to an article (also at the Library of Congress) on the FTP by Dr. Lorraine Brown of George Mason University, one of the two people responsible for discovering the FTP files in an airplane hanger in Baltimore) gave 1200 productions of at least 850 major works and of 309 new plays (29 new musicals) to an audience estimated at 25 million people in 40 states. (You can see a number of photos of FTP productions by going here.)

DEVELOPMENT OF THE FEDERAL THEATRE PROJECT

Hopkins didn’t want just a relief project, though that was important. He turned to Hallie Flanagan [this link takes you to the Library of Congress site] (1898-1969), who was a teacher and director at Grinnell College in Iowa. She had been a student in George P. Baker’s famous Workshop 47 class at Harvard; when Hopkins hired Flanagan, she was running the experimental theatre at Vassar College in New York. Hopkins hired Flanagan [this link takes you to the Billy Rose Theatre Collection at New York City's Public Library at Lincoln Center] to be the head of the Federal Theatre Project, which was divided into five areas--New York City, the East, the South, the Midwest, and the West. Flanagan had been influenced by European theatre, German Theatre and, American workers’ theatre. The Communist revolution had occurred in Russia in 1918 and many Europeans came to the U.S.; many were Communists. The Federal Theatre Project also had units in Florida, Chicago, Dallas, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Albuquerque, and many others all around the country, and eventually grossed over $2 million.

THE FEDERAL THEATRE PROJECT'S CONTROVERSIES

Despite all of its benefits, the F. T. P. was plagued by censorship, political problems, and inefficiency. The problems began to appear almost immediately: the FTP experimented with a theatre form that Flanagan had used at Vassar, called "the living newspaper" (click here for a list of available photos) --montage documentaries, carefully researched, with clear points of view, using the Epic theatre techniques of Piscator and Meyerhold’s constructivist techniques. Most Living Newspapers used a common man as their unifying character, whose curiosity about the current problem has been aroused. The character is then led through a background of the problem, which clarifies the issue for the audience. The FTP’s first Living Newspaper, planned for production in January 1936 but never produced, was called Ethiopia. The show depicted Haile Salassie, leader of Ethiopia. Washington immediately ordered that no current ministers or heads of state could be represented in the Federal Theatre Project plays, a policy that was eventually modified to allow for actual quotes, but still no depictions of real heads of state were allowed. Playwright Elmer Rice, who had taken the position as director of the New York City project, resigned over what he thought was censorship. The incident was highly publicized (Flanagan said later that the publicity may have kept the FTP as free from censorship as it was). Other living newspapers followed, however, and became what some have called one of two unique American contributions to world theatre (the other being the musical):

Triple-A Plowed Under (1936) dealing with Agricultural Administration Act, which paid farmers to ruin their own crops;

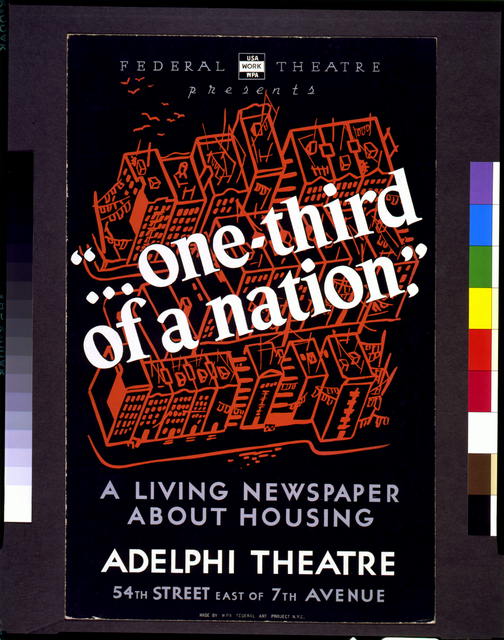

One Third of a Nation (1938), based on a pledge Roosevelt made in his second inaugural address to feed and house the nation;

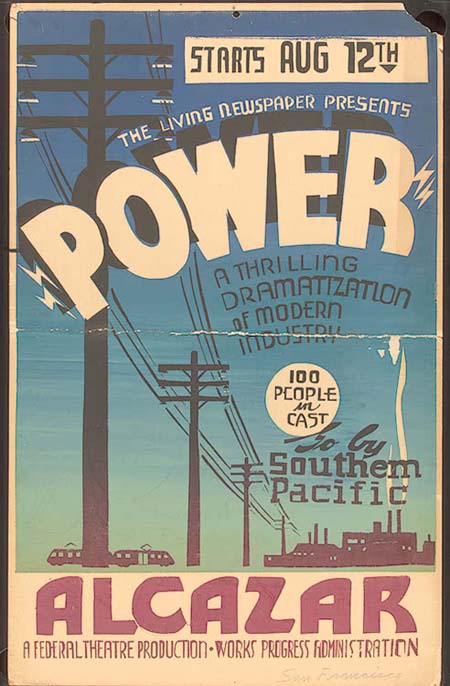

Power (1937), about monopolies of power companies and about the Tennessee Valley Authority;

and Spirochete (1937), about the problem of Syphilis.

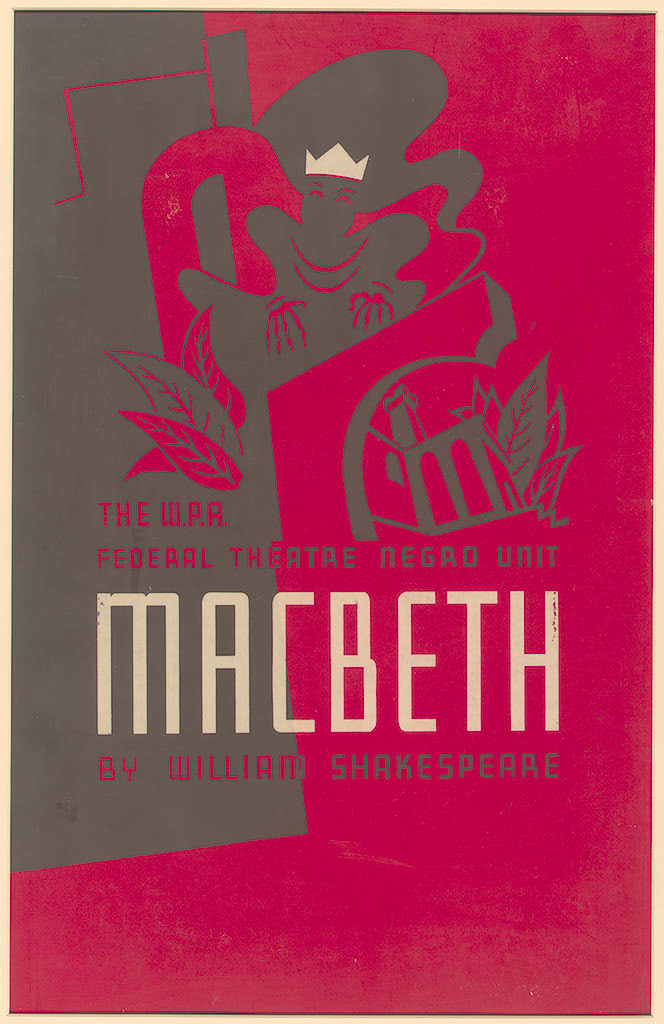

THE "NEGRO UNITS"

The "Negro Units" of the Federal Theatre Project were headed by Rose McClendon, a well-known black actress, and John Houseman, a theatre producer who was able to get actor/director Orson Welles to work with the unit. (10 percent of the Federal Theatre Project budget could be used to pay non-relief workers). There were Negro units in many cities, but the most notorious was New York’s: it produced a Swing Mikado, a swing version of the Gilbert and Sullivan show, Negro spokesman and author W. E. B. DuBois’s Haiti, and, perhaps the most famous,

the Voodoo Macbeth, for which Welles brought in actual "witch doctors" from the Caribbean (click here for some photos and here for even more photos and other fascinating material).

SOCIALLY SIGNIFICANT PLAYS

It Can’t Happen Here, a dramatization of Sinclair Lewis’s novel, opened on October 27, 1936, in 17 different locations simultaneously around the United States, including one black production. The show dealt with an imaginary fascist takeover in the United States; Flanagan wanted lots of publicity with this show and doing so many productions at the same time did the trick.

The Cradle Will Rock was rehearsed by Welles’s and Houseman’s FTP unit to be produced in June of 1937.

Marc Blitzstein wrote this show, which is more like an opera than anything else, about Larry Foreman, a worker in Steeltown (played in the original production by Howard da Silva), which is run by the boss, Mister Mister (played in the original production by Will Geer -- Grandpa in "The Waltons").

The show clearly had left-wing and unionist sympathies (Foreman ends the show with a song about "onions" taking over the town and the country), and has become legendary as an example of a "censored" show. Shortly before the show was to open, FTP officials in Washington announced that no productions would open until after July 1, 1937, the beginning of the new fiscal year. John Houseman writes in his book Runthrough about the circumstances surrounding the opening of the show.

Photo: The Cradle Will Rock in rehearsal

All the performers had been enjoined not to perform on stage for the production when it opened on July 14, 1937. The cast and crew left their government-owned theatre and walked 20 blocks to another theatre, with the audience following. No one knew what to expect; when they got there Blitzstein himself was at the piano and started playing the introduction music. One of the non-professional performers, Olive Stanton, who played the part of Moll, the prostitute, stood up in the audience, and began singing her part. All the other performers, in turn, stood up for their parts. Thus the "oratorio" version of the show was born. Apparently, Welles had designed some intricate scenery, which ended up never being used. Welles and Houseman left the FTP shortly after that, and formed the Mercury Theatre (later to become famous for their controversial War of the Worlds radio broadcast, which had put much of the country in a panic), performed Cradle on Sundays, and later took the show to Broadway.

Revolt of the Beavers. The Federal Theatre Project also had active Children's Theatre units; they were not immune to criticism, either. One of the most infamous children's plays was Revolt of the Beavers -- criticized for its socialistic viewpoint (click the image or title above to see more information).

Sing for your Supper was the production that became the most visibly and publicly condemned by Congress, which eventually led to the closing of the Federal Theatre Project. The show opened in the spring of 1939 (the opening date is disputed in various sources), after eighteen months of rehearsal. (Brooks Atkinson's review of the show in the New York Times was entitled, "Federal Theatre's 'Sing For Your Supper' Officially Concludes Rehearsal Period" [25 April 1939, 18:6]).

The long rehearsal period was a caused by a number of factors and led to even further condemnation by a Congress determined to close the FTP down: actors would be seen by agents and get hired for other shows; the FTP then had to find other performers and rehearse with them; and in the meantime other performers would find other jobs. Adding this to the red tape involved in getting funding and approval for any changes, it is remarkable that the show went up at all.

Supper closed on the last day of the FTP’s existence, June 30, 1939. It was a topical revue about what the performers were doing--they were indeed singing for their supper, which would be paid for by the federal government.

THE DEMISE OF FEDERAL THEATRE PROJECT

Partly because of its 18-month-long rehearsal time, and partly because of long-held suspicions that the FTP was fraught with Communists and fellow travelers, Congress shut it down. Republican member of Congress, Martin Dies, became the head of a new committee, the House Un-American Activities Committee, charged to find those in and out of government participating in un-American Activities (this committee would, of course, continue through the forties and into the ‘50s, until it was eventually stifled by the negative publicity of Congress-member Joseph McCarthy). Dies deplored the FTP’s inefficiency, extravagance, and political satire, along with its lewdness, waste, and leftism, calling it a propaganda machine.

Members of this committee certainly didn’t know much about theatre: when Flanagan mentioned, during testimony, the name of Christopher Marlowe, one member of Congress asked whether Marlowe was a Communist. Despite their ignorance (my editorial: or perhaps because of it), Congress removed all funds from FTP projects. The other three Arts Projects--Music, Art, and Writing--continued to be funded by Congress until 1941.The Federal Theatre Project had brought theatre to millions who had never seen theatre before, it employed millions of people, it introduced European epic theatre and Living Newspaper theatre techniques to the United States, and hence could be seen as a great success. In fact, it is a unique development in the American theatre, whose implications are still not clear. At the very least, it has shown the debilitating effects that can occur in the United States when politicians and bureaucrats have ultimate control over what should be an artistic endeavor.

Back to the Workers' Theatre page...

THIS IS THE END OF UNIT III

**Here's a study guide for Exam Three (MS Word file / text file)...**

Now...Get an exam pass and Take Exam Three...

Click for "Introduction to Theatre on the Web" Main Page

This page and all linked pages in this directory are copyrighted © Eric W. Trumbull, 1998-2007.

Last update: November 17, 2007